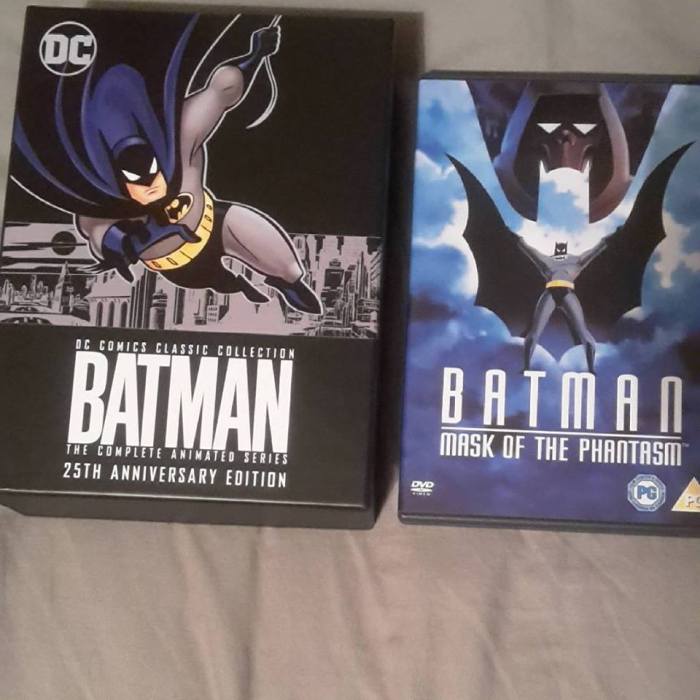

Bit of a prolonged absence from this blog since last time. Guess that little thing called life has managed to get in the way more than I thought it would. Still, to quote the title of an episode of the show I’m about to review, ‘it’s never too late’, and a renewed interest in comics that characterised most of my teens and early twenties, sparked off by receiving the complete boxset of ‘Batman: The Animated Series’ for Christmas, looks likely to see me bring a lot of new DC-related material to this page in the near future, as I work my way through producer Bruce Timm’s magnificent DC Animated Universe, and its associated comic spin-offs.

This is the definitive Batman. Nothing else remotely comes close. And that bold statement comes from someone who is a fan of the character through numerous iterations, and who has been fascinated by the many different ways in which he has been interpreted. But, it’s true. The mythology has never been done better than this. It’s certainly heartening for this reviewer to see DC, and comics in general, gain much more popularity among the mainstream than ever used to be the case when I was a child, with every Waterstones now boasting a dedicated graphic novels section, Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy searing Heath Ledger’s Joker into the public consciousness, the Arkham games introducing the general public to the rest of the rogues gallery like never before, and 2016’s ‘Suicide Squad’ launching Harley Quinn into the pop-culture stratosphere as, essentially, the fourth pillar of the DC brand, alongside Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman. But, wonderful as it is to have this new generation of fans onboard, with superheroes no longer the specialist domain of Forbidden Planet stores, they didn’t have the utter pleasure and privilege of being raised on the show I’m about to review. They didn’t have the experience of lying on their living room sofa as a young boy or girl, recovering from illness by watching episode after episode on Cartoon Network, witnessing the Caped Crusader’s silhouette lighting up against the night sky during a storm at the end of the incredible opening sequence. This series, this Batman, this timeless, surreal Art Deco-inspired world of Gotham devised by producer Eric Radomski, was absolutely formative for me, and has shaped my views and expectations of the character ever since. And I am so very glad it did.

The complete series boxset includes the revamped ‘New Batman Adventures’ that aired some three years after the original episodes, but, for now, this review will simply cover the initial two seasons and their spin-off movies, given how beautifully they work when considered as a self-contained story in their own right. As great as the rest of the DCAU is, some of it does undo the power of that original series when viewed as a complete mythology, and so, for this reviewer at least, anything from the ‘New Adventures’ onwards is perhaps best considered as a brilliant ‘Elseworlds’ (or ‘what if’, for non-comic buffs) story, rather than a definite continuation of the original episodes (not least because of the dramatic change in style of the characters and their surroundings in those later series, their world brought into a much more modern time period, rather than the beautifully ambiguous, part-forties gangster noir, part-thirties architecture, part-sixties sci-fi aesthetic of the original series).

Consisting of two seasons and two feature spin-offs, running from 1992 to 1995, ‘Batman: The Animated Series’ initially takes its inspiration from the Tim Burton movies, everything from Batman and the Joker’s costumes, to the Penguin’s grotesque design, to the Danny Elfman score over the opening and closing titles, before giving way to something very much its own, with the unspeakably talented Shirley Walker soon dropping Elfman’s musical cues to craft, in my opinion, the greatest Batman theme ever composed, a soaring nine-note motif that captures the Gothic majesty of the character, and one she brilliantly tweaks to be either tragic (the ‘Mask of the Phantasm’ soundtrack), or uplifting (the later ‘Adventures of Batman and Robin’ opening credits). Complementing this main score is an array of glorious, hum-able themes for all the supporting characters and villains. Elfman’s Batman music is great. Every note of Walker’s is art.

I’ve already alluded to Radomski’s production design. This is a Gotham you want to immerse yourself in, and, for all its in-world danger, and despite the fact it’s two-dimensional animation, live in. With black paper backgrounds for the animation (unheard of prior to the show), and a hyper-stylised, part-period, part-futuristic architectural look, this Gotham is dark, rich, fascinating and compelling in every frame. Watch Batman perch atop a cathedral in ‘It’s Never Too Late’, walk up to the grave of his parents in ‘Mask of the Phantasm’, or abduct a petty criminal high into the moonlit sky with the Batwing in ‘Feat of Clay’, and tell me this isn’t an extraordinarily-realised world. Treat yourself to a trio of episodes a night (what I’ve been doing since Christmas), and you’ll be hungry and impatient to dive back into this universe the next evening.

On a side note, a primary example of the love and thought that went into this original series has to be the brilliant opening title cards (something that wouldn’t feature again in the revamped episodes). Seeing these titles, accompanied by visuals and stirring music from Walker that would sometimes give a clue as to the villain of the episode, and sometimes wouldn’t, whets the appetite like nothing else I can think of in a cartoon, and all are works of art in their own right- a sumptuous starter before the main course of the episode.

For all that these production elements deserve praise, however, they merely set the scene, creating a rich backdrop against which writers and actors can show their craft. And what craft.

The writing. My God, the writing. This is a series that manages to be every bit as engaging for adults as it is for children. The latter, including my younger self, will be thrilled by the action, the gadgets, the fights, the colourful villains. The former, my current self included, will marvel at the intellectual and emotional intelligence, the pathos, the plotting, the smart one-liners. This is not a cartoon that any grown-up need be embarrassed about watching without the presence of children. It is a series that rewards you for trusting it with your intelligence. And rewards you well.

No review could ever be long enough to appraise every good story in the series, so a subjective handful will have to suffice. Already mentioned a couple of times this review, and for good reason, ‘It’s Never Too Late’ is a haunting, human, thoughtful piece of fiction that delves into the morality of gangster lifestyles and drug dealing with a poignancy many live-action series would struggle to match. The much-lauded, Emmy-winning ‘Heart of Ice’ gives a backstory to previously one-note villain Mr Freeze that has subsequently been adapted into the canon of the comics. ‘Feat of Clay’ is a Shakespearean tragedy of a man destroyed by weakness and cruel fate, only to be brought back as a literal monster, and is probably the finest two-parter the series ever produced. ‘Joker’s Favour’ might very well be the best Joker story in any version of the Batman mythology, ingeniously viewing the villain through the lens of an ordinary man on the ground left terrorised by his sadistic whims, as well as having the honour of introducing, via creator Paul Dini, the now-iconic character of Harley Quinn, who soon made her way into the main comics, and whose ascent has only continued. ‘Perchance to Dream’ gives us a great ‘what if’ insight into what Bruce Wayne’s life might look like if that fateful night that killed his parents had never occurred. ‘Almost Got ‘Im’ is sheer, unadulterated fun from start to finish, treating us to the rogues gallery playing poker around the table in a dingy club hideaway, and one-upping each other with tales of how they almost bested the Dark Knight. ‘Trial’ takes this fun factor of all the villains together one step further, and sees them actively team up to put their joint nemesis through hell, within the walls of the asylum he is responsible for putting them all in. And ‘House and Garden’, one of the series’ last episodes, has probably been the biggest surprise for this reviewer upon rewatching- a Poison Ivy story that manages to be both chillingly creepy, and poignantly sad, and has lingered in my mind as, quite possibly, my personal favourite episode of the boxset.

Meanwhile, special mention must go to the first spin-off movie, ‘Mask of the Phantasm’. Originally released in cinemas (regrettably without sufficient marketing to make it a box-office success, but happily having acquired a cult status on home video since) between the first and second seasons, this movie was a staple of my childhood, and for good reason. By turns an origin saga, murder mystery, and sweeping love story, it again rewards the viewer’s intelligence with smart plotting and strong characterisation (watch the scene of Bruce at the graveside in the rain), and features Shirley Walker’s best work of the series. Meanwhile, it manages the remarkable feat, in quite spooky fashion, of telling us a lot about the Joker’s origin, without actually really telling us anything. The second feature spin-off, ‘Subzero’ (direct to video this time), is also a good film, but ‘Phantasm’ is simply untouchable for sheer quality, and is rapidly, and rightly, acquiring a reputation among fans as the best Batman movie ever made.

The writing, however, extraordinary as it is, would mean little without a strong voice cast to go with it.

What a cast.

Kevin Conroy’s Batman. Deep, without resorting to the live-action growls of Christian Bale, he brings a gravitas and authority to the character that really makes you understand why the criminals of Gotham would cower the second he opens his mouth, and yet manages a warmth and humour around his allies, even without the lighter, put-on ‘Bruce Wayne’ voice he adopts when pretending to be a slightly dim playboy, that should seem impossible from the same person. Loren Lester’s fun, wisecracking Robin, the show’s smart decision to age the character up enough for him to be in college, helps you understand both how Dick Grayson manages to be a healthy foil to Batman’s darkness, and how he goes on, as Nightwing, to be such a draw for the women of the DC Universe. Efrem Zimbalist Jr.’s warm and witty Alfred is the soothing presence you can imagine keeps Batman sane and grounded in this otherwise mad, dangerous world of crime and mayhem. Bob Hastings’ paternal Commissioner Gordon is a man you can buy Bruce Wayne viewing as a surrogate father. Elsewhere, Robert Costanzo’s just-the-right-side-of-slimy Detective Bullock, and Melissa Gilbert’s spirited Batgirl.

And then, the villains. What a roster of voice talent. King among them all, Mark Hamill’s magnificent Joker. Forget Nicholson or Ledger. This is the definitive Clown Prince of Crime. Forever striding a fine line between genuinely funny and sadistically evil, lending itself to a sense of never quite knowing which way he’ll tip at any given time, and subsequently creating tension for the viewer, Hamill injects the part with an energy that lays bare his delight in having secured the role, originally only signed up for a bit part in ‘Heart of Ice’. At heart (at least according to interviews) more a character actor than a leading man, the Joker is Hamill’s dream role, and God, does it show.

Alongside him, Arleen Sorkin’s batshit-crazy Harley Quinn, second only to the Ace of Knaves himself in the dangerously unpredictable stakes. Quirky and fun some episodes, fierce and deranged others, Quinn fits into the mythos so well, both as Joker’s moll and as a villain in her own right, that it seems strange that she spent decades not being part of it.

Elsewhere, Adrienne Barbeau’s sultry Catwoman. More idealistic in her guise of Selina Kyle, but even then carrying an undercurrent of danger, Barbeau makes us believe that Batman, for all his attraction to her, can never quite drop his guard around the woman who is both love interest and foe, never quite able to be sure of her motives (an uncertainty finally, and poignantly, resolved in the excellent ‘Catwalk’).

Richard Moll’s snarling, sinister Harvey Dent, unnerving, even before his transformation into Two-Face, as repressed dark personality Big Bad Harv (a scene in a psychiatrist’s office, lightning flashing outside the window, in ‘Two-Face Part 1′ sends a shiver down the spine). Paul Williams’ sophisticated Penguin, armed just as readily with one liners as poison-tipped umbrellas, and all the more unsettling juxtaposed with the character’s gruesome ‘Batman Returns’-inspired appearance (later toned down for the revamped episodes). John Glover’s sardonic, superior Riddler, his confident, quietly dangerous take easily my favourite interpretation of the character, no need here for the deranged mania of other versions (*looks at ‘Batman Forever’*). Henry Polic II’s cruel, callous Scarecrow, the sense of a character genuinely delighting in the fear of others. John Vernon’s oily, loathsome Rupert Thorne. Diane Pershing’s driven, fanatical Poison Ivy, possibly the strongest female vocal performance in the cast (listen to her wicked laugh in ‘Harley and Ivy’, as Joker’s attempted ambush with the poisonous flower on his lapel goes very wrong). Ron Perlman’s angry, desperate, drug-addict analogy Clayface. Michael Ansara’s cold (no pun intended), calculating, yet laced with just a hint of lingering, buried emotion, Mr Freeze. Roddy McDowall’s obsessive, delusional Mad Hatter. Aron Kincaid’s guttural, suitably reptilian Killer Croc. David Warner’s hypnotic, eerie Ra’s al Ghul. Helen Slater’s beguiling, ambiguous Talia.

There are others, of course, but some villains really only get an episode or two to serve as story of the week threats. The above represent the recurring rogues gallery, and together, form a rich tapestry of villainy for Batman to fight. It means, more often than not (although a surprising amount of episodes don’t feature any costumed villains at all) that whenever you play an episode, you’re going to be treated to epic exchanges between Conroy and one of the aforementioned actors, no matter who the villain of the story turns out to be.

It’s not perfect. There are dud episodes. ‘The Last Laugh’ is an unfortunately early poor Joker entry in a series stacked full of great ones. ‘Prophecy of Doom’ holds the questionable honour of introducing possibly the worst Batman villain ever created in Nostromo (although even it has a redeeming feature in the shape of a great climactic action sequence). ‘Heart of Steel’, all the more regrettable for being a two-parter, and despite the cool concept of an AI villain, fails to stir the imagination as it should. ‘Baby Doll’ sees its attempt to establish a brand new villain for the mythos backfire where ‘Joker’s Favour’ succeeds in Harley Quinn. And the less said about the ‘Allo, Guvnor’ portrayal of London in ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’, the better. Meanwhile, returning to the series as an adult, and despite this reviewer’s distaste for the casual, grotesque murder and death of more modern interpretations of the mythology like Fox’s ‘Gotham’, it is very noticeable how the show pulls back from ever letting anyone die (bar the two spin-off movies). Loss of life, even for rank and file henchmen, is absolutely off limits, and by the end of the two seasons, it does start to feel very contrived when yet another Joker goon manages to crawl to safety from burning wreckage.

These flaws, however, are the rare exception to a very strong rule. ‘Batman: The Animated Series’ is a love letter to the Caped Crusader, a pure distillation of all that is best about the character. Borrowing a little of the Burton movies here, a little of Adam West or the source comics there, while ultimately forging its own identity, the series is, to my mind, as close as it is possible to get to the essence of Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s creation. It feels as timeless now, watching in 2018, as it did on that sofa as a child in the mid-nineties. I’m not sure there’ll ever be a more perfect bringing to life of a comic book. I’m pretty sure this was it.

*****

Dark, intelligent, mature storytelling, whilst still managing to be fun and adventurous, ‘Batman: The Animated Series’ is every bit as great a watch for adults as it is for children. Surely the greatest comic book adaptation ever produced.

Christopher Moore

@Moore_27Chris